publications

2025

-

Detecting interspecific positive selection using convolutional neural networksCharlotte West, Conor R. Walker, Shayesteh Arasti, Viacheslav Vasilev, Xingze Xu, Nicola De Maio, and Nick GoldmanMolecular Biology and Evolution, Jun 2025

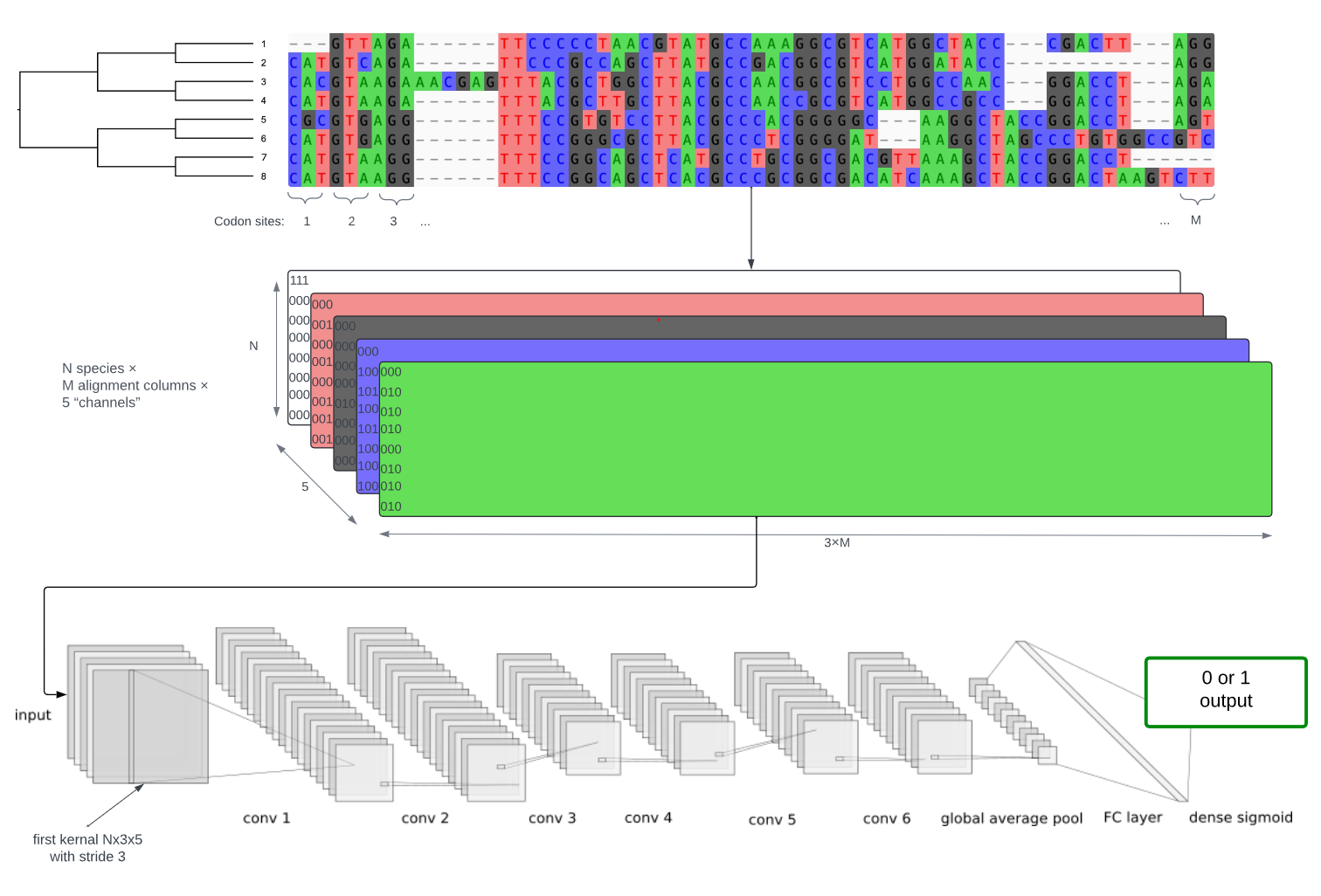

Detecting interspecific positive selection using convolutional neural networksCharlotte West, Conor R. Walker, Shayesteh Arasti, Viacheslav Vasilev, Xingze Xu, Nicola De Maio, and Nick GoldmanMolecular Biology and Evolution, Jun 2025Traditional statistical methods using maximum likelihood and Bayesian inference can detect positive selection from an interspecific phylogeny and a codon sequence alignment based on model assumptions, but they are prone to false positives due to alignment errors and can lack power. These problems are particularly pronounced when faced with high levels of indels and divergence. To address these issues, we trained and tested convolutional neural network (CNN) models on simulated data and achieved higher accuracy in detecting selection across a specific range of phylogenetic scenarios and evolutionary modes. This advantage is particularly evident when performing inference on noisy data prone to misalignments. Our method shows some ability to account for these errors, where most statistical frameworks fail to do so in a tractable manner. We explore the generalisability of our CNN models to unseen evolutionary scenarios and identify future avenues to achieve broader utility. Once trained, our CNN model is faster at test time, making it a scalable alternative to traditional statistical methods for large-scale, multi-gene analyses. In addition to binary classification (inference of the presence or absence of positive selection during the evolution of the sequences), we use saliency maps to understand what the model learns and observe how this could be leveraged for sitewise inference of positive selection.

-

Secure and scalable gene expression quantification with pQuantSeungwan Hong, Conor R. Walker, Yoolim A. Choi, and Gamze GürsoyNature Communications, Mar 2025

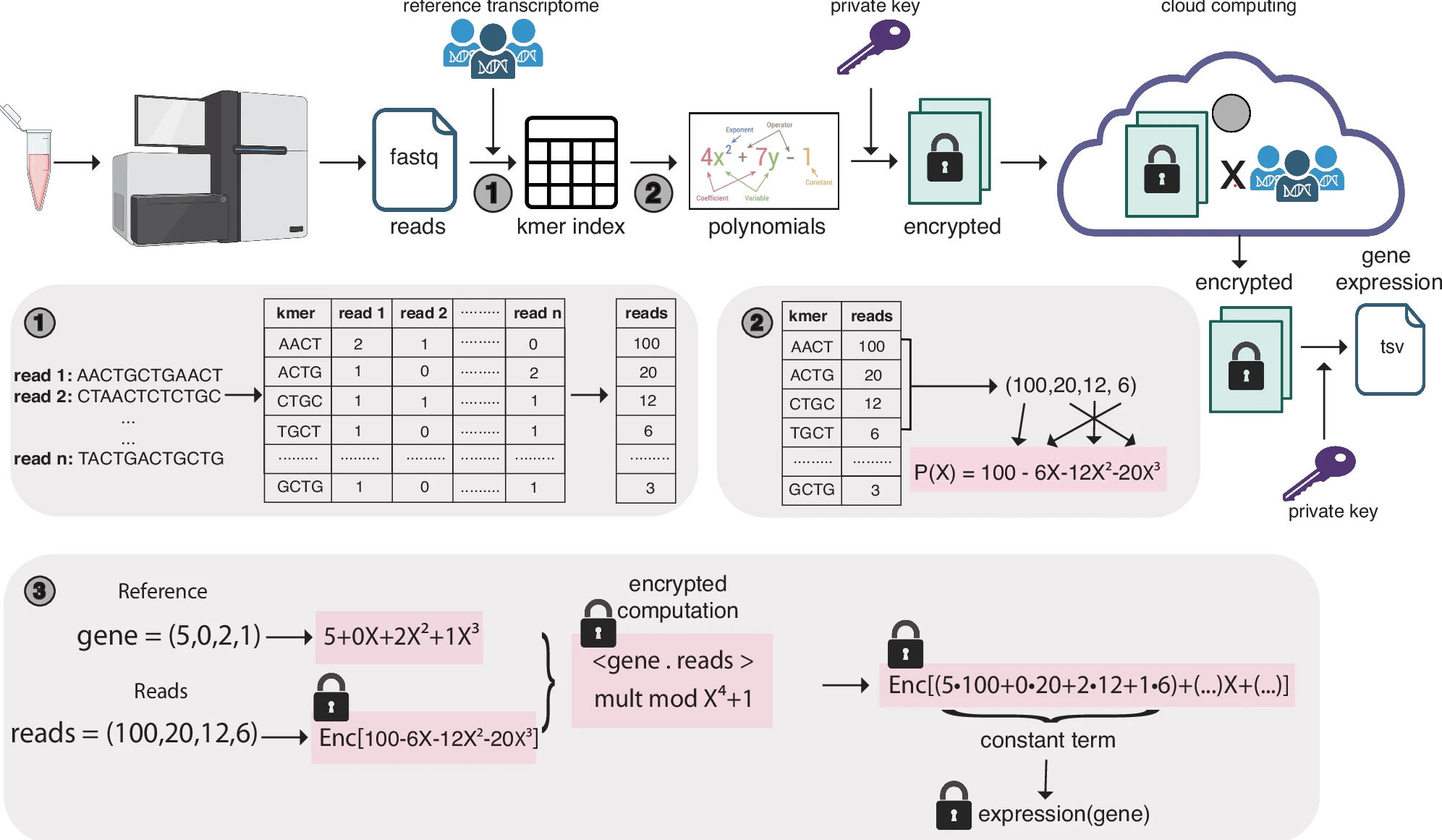

Secure and scalable gene expression quantification with pQuantSeungwan Hong, Conor R. Walker, Yoolim A. Choi, and Gamze GürsoyNature Communications, Mar 2025Next generation sequencing reads from RNA-seq studies expose private genotypes of individuals during computation. Here, we introduce pQuant, an algorithm that employs homomorphic encryption to ensure privacy-preserving quantification of gene expression from RNA-seq data across public and cloud servers. pQuant performs computations on encrypted data, allowing researchers to handle sensitive information without exposing it. Our evaluations demonstrate that pQuant achieves accuracy comparable to state-of-the-art non-secure algorithms like STAR and kallisto. pQuant is highly scalable and its runtime and memory do not depend on the number of reads. It also supports parallel processing to enhance efficiency regardless of the number of genes analyzed.

2024

-

Private information leakage from single-cell count matricesConor R. Walker, Xiaoting Li, Manav Chakravarthy, William Lounsbery-Scaife, Yoolim A. Choi, Ritambhara Singh, and Gamze GürsoyCell, Nov 2024

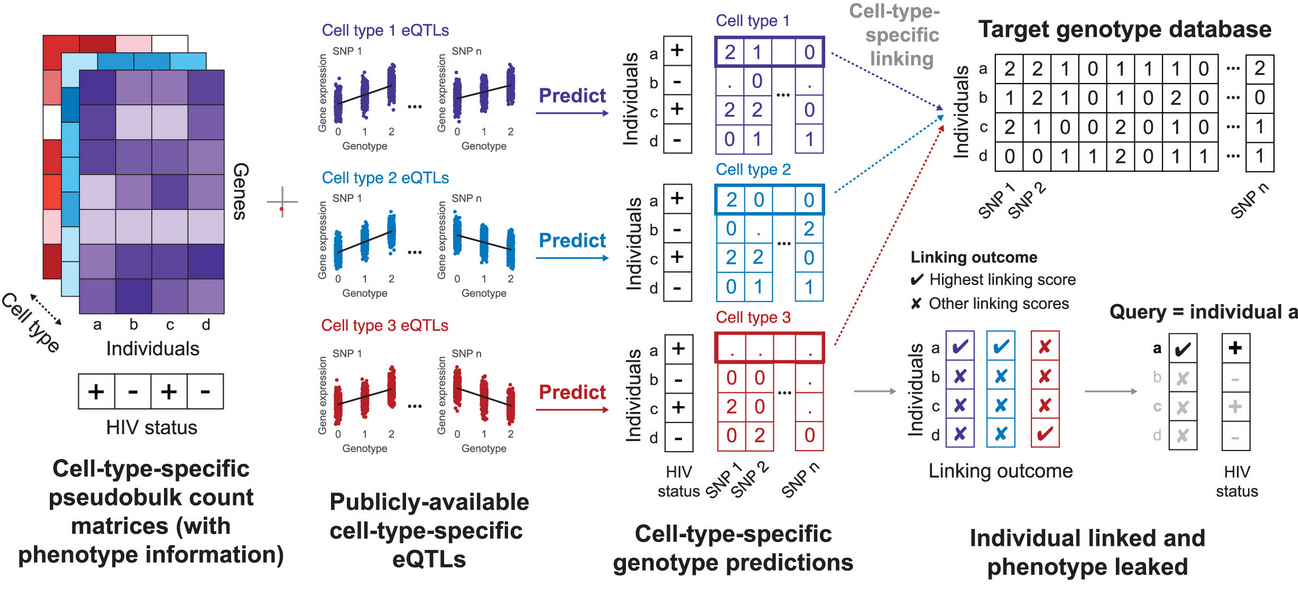

Private information leakage from single-cell count matricesConor R. Walker, Xiaoting Li, Manav Chakravarthy, William Lounsbery-Scaife, Yoolim A. Choi, Ritambhara Singh, and Gamze GürsoyCell, Nov 2024The increase in publicly available human single-cell datasets, encompassing millions of cells from many donors, has significantly enhanced our understanding of complex biological processes. However, the accessibility of these datasets raises significant privacy concerns. Due to the inherent noise in single-cell measurements and the scarcity of population-scale single-cell datasets, recent private information quantification studies have focused on bulk gene expression data sharing. To address this gap, we demonstrate that individuals in single-cell gene expression datasets are vulnerable to linking attacks, where attackers can infer their sensitive phenotypic information using publicly available tissue or cell-type-specific expression quantitative trait loci (eQTLs) information. We further develop a method for genotype prediction and genotype-phenotype linking that remains effective without relying on eQTL information. We show that variants from one study can be exploited to uncover private information about individuals in another study.

-

Paired CRISPR screens to map gene regulation in cis and transXinhe Xue, Zoran Z. Gajic, Christina M. Caragine, Mateusz Legut, Conor R. Walker, James Y.S. Kim, Xiao Wang, Rachel E. Yan, Hans-Hermann Wessels, Congyi Lu, Neil Bapodra, Gamze Gürsoy, and Neville E. SanjanabioRxiv, Nov 2024

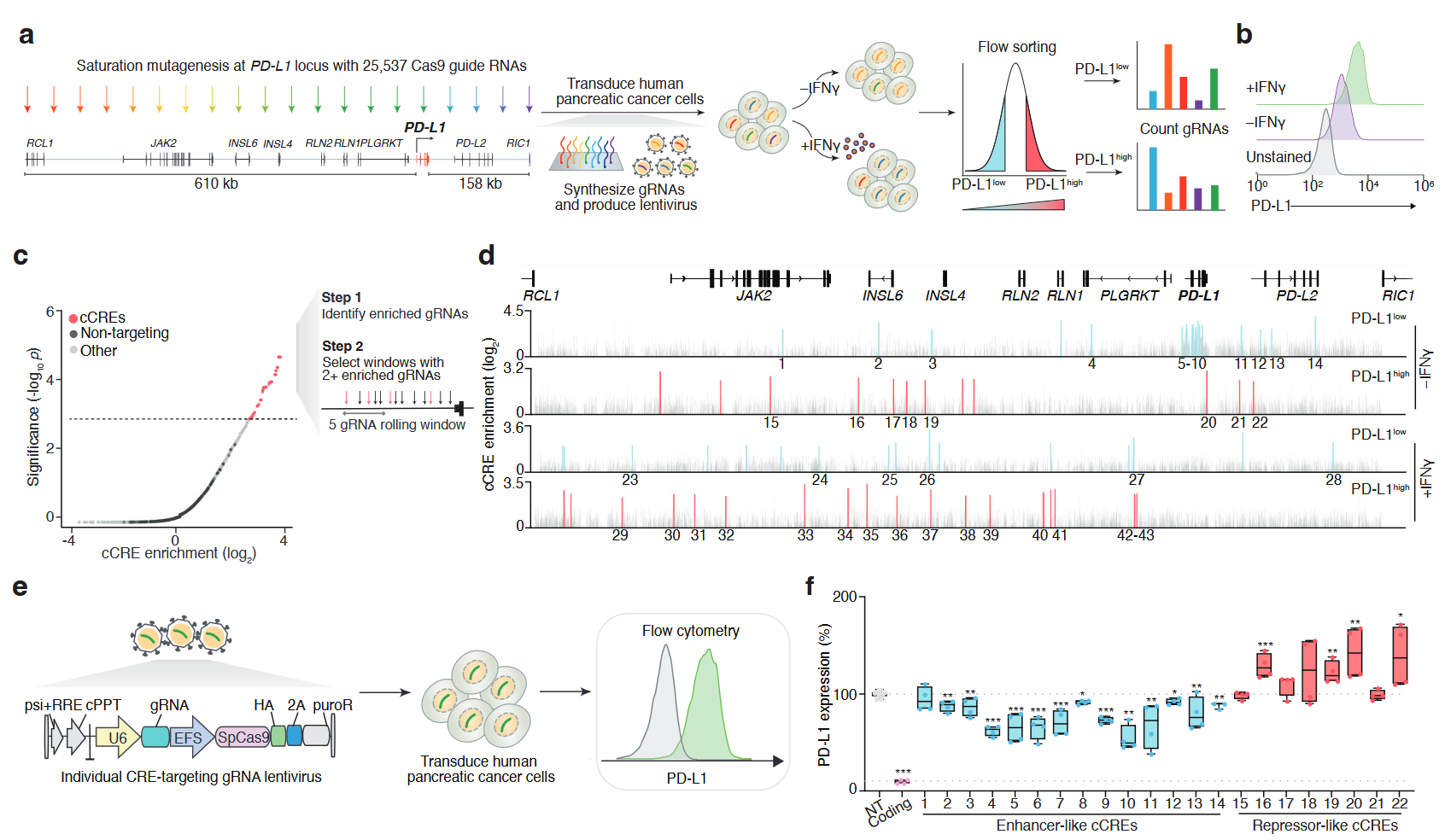

Paired CRISPR screens to map gene regulation in cis and transXinhe Xue, Zoran Z. Gajic, Christina M. Caragine, Mateusz Legut, Conor R. Walker, James Y.S. Kim, Xiao Wang, Rachel E. Yan, Hans-Hermann Wessels, Congyi Lu, Neil Bapodra, Gamze Gürsoy, and Neville E. SanjanabioRxiv, Nov 2024Recent massively-parallel approaches to decipher gene regulatory circuits have focused on the discovery of either cis-regulatory elements (CREs) or trans-acting factors. Here, we develop a scalable approach that pairs cis- and trans-regulatory CRISPR screens to systematically dissect how the key immune checkpoint PD-L1 is regulated. In human pancreatic ductal adenocarcinoma (PDAC) cells, we tile the PD-L1 locus using ~25,000 CRISPR perturbations in constitutive and IFNγ-stimulated conditions. We discover 67 enhancer- or repressor-like CREs and show that distal CREs tend to contact the promoter of PD-L1 and related genes. Next, we measure how loss of all ~2,000 transcription factors (TFs) in the human genome impacts PD-L1 expression and, using this, we link specific TFs to individual CREs and reveal novel PD-L1 regulatory circuits. For one of these regulatory circuits, we confirm the binding of predicted trans-factors (SRF and BPTF) using CUT&RUN and show that loss of either the CRE or TFs potentiates the anti-cancer activity of primary T cells engineered with a chimeric antigen receptor. Finally, we show that expression of these TFs correlates with PD-L1 expression in vivo in primary PDAC tumors and that somatic mutations in TFs can alter response and overall survival in immune checkpoint blockade-treated patients. Taken together, our approach establishes a generalizable toolkit for decoding the regulatory landscape of any gene or locus in the human genome, yielding insights into gene regulation and clinical impact.

2022

-

phastSim: efficient simulation of sequence evolution for pandemic-scale datasetsNicola De Maio, William Boulton, Lukas Weilguny, Conor R. Walker, Yatish Turakhia, Russell Corbett-Detig, and Nick GoldmanPLOS Computational Biology, Apr 2022

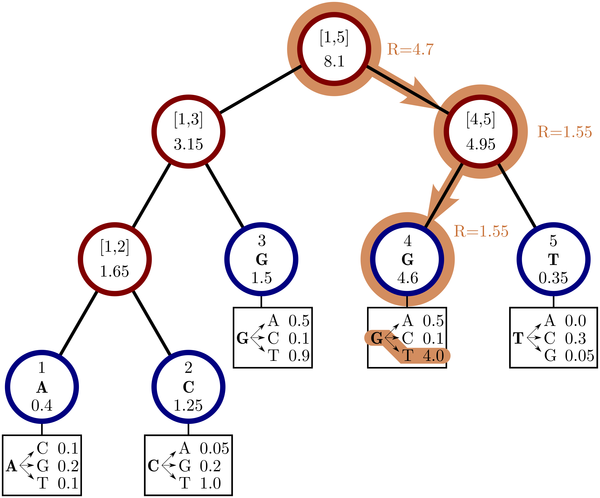

phastSim: efficient simulation of sequence evolution for pandemic-scale datasetsNicola De Maio, William Boulton, Lukas Weilguny, Conor R. Walker, Yatish Turakhia, Russell Corbett-Detig, and Nick GoldmanPLOS Computational Biology, Apr 2022Sequence simulators are fundamental tools in bioinformatics, as they allow us to test data processing and inference tools, and are an essential component of some inference methods. The ongoing surge in available sequence data is however testing the limits of our bioinformatics software. One example is the large number of SARS-CoV-2 genomes available, which are beyond the processing power of many methods, and simulating such large datasets is also proving difficult. Here, we present a new algorithm and software for efficiently simulating sequence evolution along extremely large trees (e.g. > 100, 000 tips) when the branches of the tree are short, as is typical in genomic epidemiology. Our algorithm is based on the Gillespie approach, and it implements an efficient multi-layered search tree structure that provides high computational efficiency by taking advantage of the fact that only a small proportion of the genome is likely to mutate at each branch of the considered phylogeny. Our open source software allows easy integration with other Python packages as well as a variety of evolutionary models, including indel models and new hypermutability models that we developed to more realistically represent SARS-CoV-2 genome evolution.

2021

-

Mutation rates and selection on synonymous mutations in SARS-CoV-2Nicola De Maio, Conor R. Walker, Yatish Turakhia, Robert Lanfear, Russell Corbett-Detig, and Nick GoldmanGenome Biology and Evolution, Apr 2021evab087

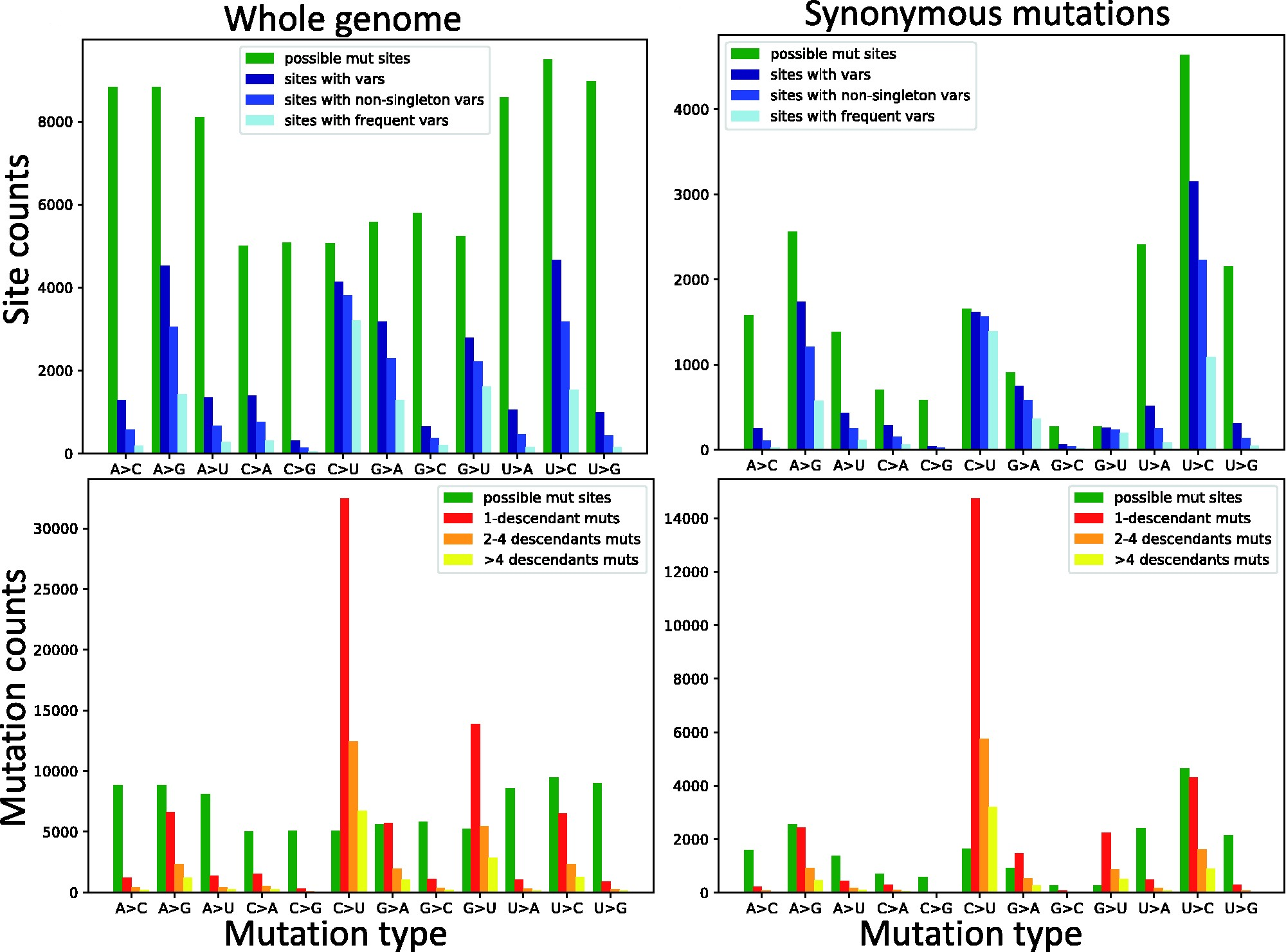

Mutation rates and selection on synonymous mutations in SARS-CoV-2Nicola De Maio, Conor R. Walker, Yatish Turakhia, Robert Lanfear, Russell Corbett-Detig, and Nick GoldmanGenome Biology and Evolution, Apr 2021evab087The COVID-19 pandemic has seen an unprecedented response from the sequencing community. Leveraging the sequence data from more than 140,000 SARS-CoV-2 genomes, we study mutation rates and selective pressures affecting the virus. Understanding the processes and effects of mutation and selection has profound implications for the study of viral evolution, for vaccine design, and for the tracking of viral spread. We highlight and address some common genome sequence analysis pitfalls that can lead to inaccurate inference of mutation rates and selection, such as ignoring skews in the genetic code, not accounting for recurrent mutations, and assuming evolutionary equilibrium. We find that two particular mutation rates, G →U and C →U, are similarly elevated and considerably higher than all other mutation rates, causing the majority of mutations in the SARS-CoV-2 genome, and are possibly the result of APOBEC and ROS activity. These mutations also tend to occur many times at the same genome positions along the global SARS-CoV-2 phylogeny (i.e., they are very homoplasic). We observe an effect of genomic context on mutation rates, but the effect of the context is overall limited. Although previous studies have suggested selection acting to decrease U content at synonymous sites, we bring forward evidence suggesting the opposite.

-

Short-range template switching in great ape genomes explored using pair hidden Markov modelsConor R. Walker, Aylwyn Scally, Nicola De Maio, and Nick GoldmanPLOS Genetics, Mar 2021

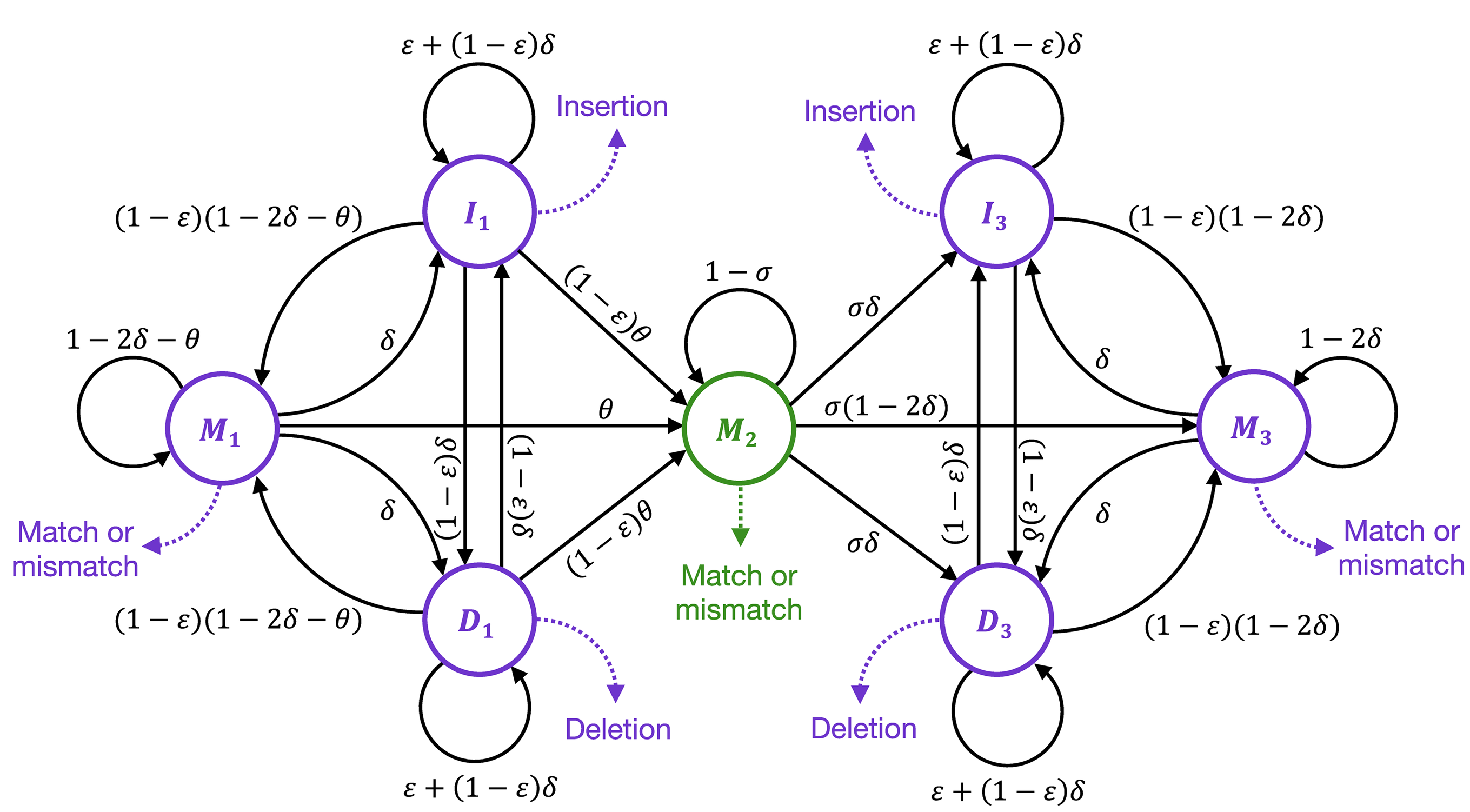

Short-range template switching in great ape genomes explored using pair hidden Markov modelsConor R. Walker, Aylwyn Scally, Nicola De Maio, and Nick GoldmanPLOS Genetics, Mar 2021Many complex genomic rearrangements arise through template switch errors, which occur in DNA replication when there is a transient polymerase switch to an alternate template nearby in three-dimensional space. While typically investigated at kilobase-to-megabase scales, the genomic and evolutionary consequences of this mutational process are not well characterised at smaller scales, where they are often interpreted as clusters of independent substitutions, insertions and deletions. Here we present an improved statistical approach using pair hidden Markov models, and use it to detect and describe short-range template switches underlying clusters of mutations in the multi-way alignment of hominid genomes. Using robust statistics derived from evolutionary genomic simulations, we show that template switch events have been widespread in the evolution of the great apes’ genomes and provide a parsimonious explanation for the presence of many complex mutation clusters in their phylogenetic context. Larger-scale mechanisms of genome rearrangement are typically associated with structural features around breakpoints, and accordingly we show that atypical patterns of secondary structure formation and DNA bending are present at the initial template switch loci. Our methods improve on previous non-probabilistic approaches for computational detection of template switch mutations, allowing the statistical significance of events to be assessed. By specifying realistic evolutionary parameters based on the genomes and taxa involved, our methods can be readily adapted to other intra- or inter-species comparisons.

2020

-

A phylodynamic workflow to rapidly gain insights into the dispersal history and dynamics of SARS-CoV-2 lineagesSimon Dellicour, Keith Durkin, Samuel L Hong, Bert Vanmechelen, Joan Martí-Carreras, Mandev S Gill, Cécile Meex, Sébastien Bontems, Emmanuel André, Marius Gilbert, Conor R. Walker, Nicola De Maio, Nuno R Faria, James Hadfield, Marie-Pierre Hayette, Vincent Bours, Tony Wawina-Bokalanga, Maria Artesi, Guy Baele, and Piet MaesMolecular Biology and Evolution, Mar 2020

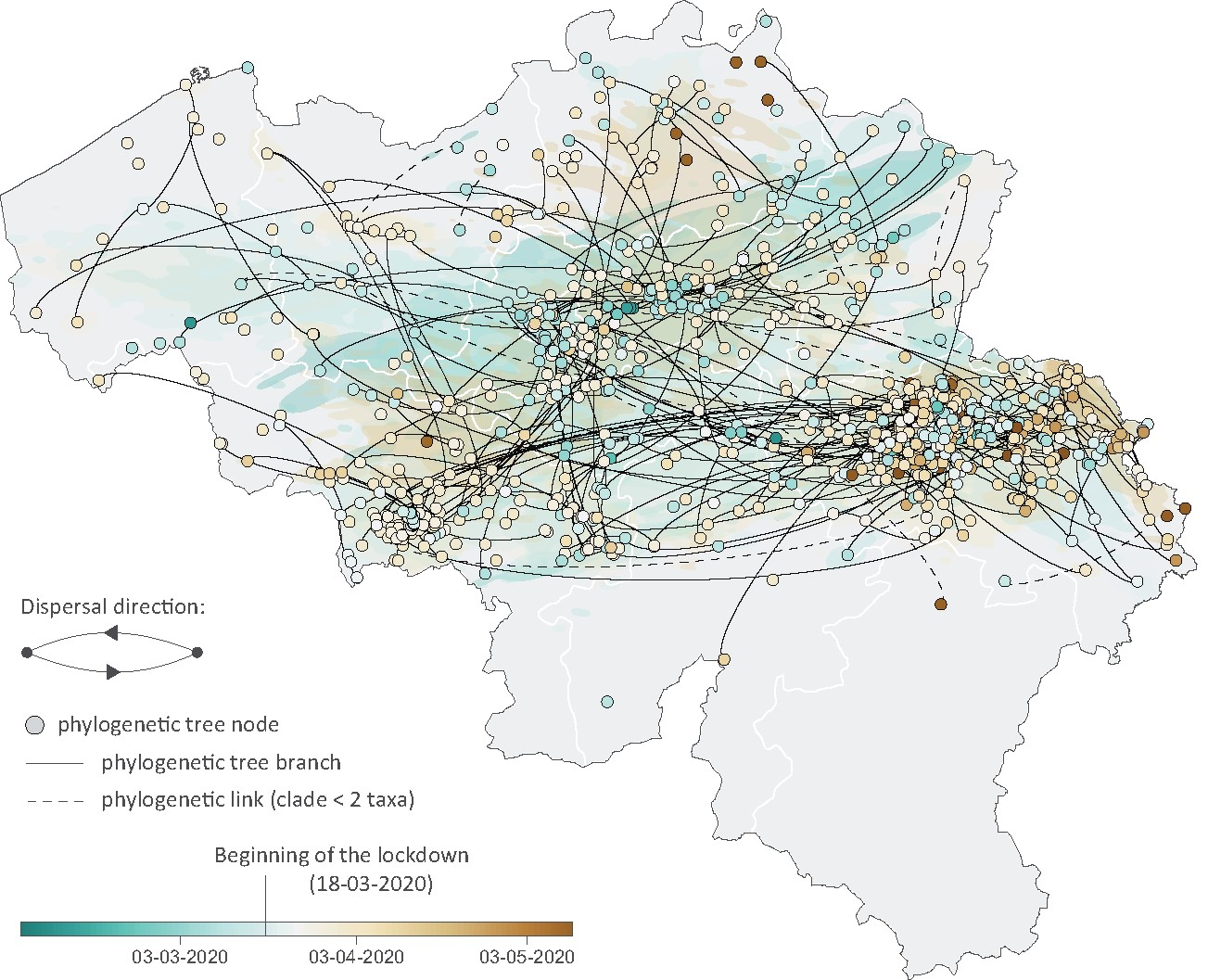

A phylodynamic workflow to rapidly gain insights into the dispersal history and dynamics of SARS-CoV-2 lineagesSimon Dellicour, Keith Durkin, Samuel L Hong, Bert Vanmechelen, Joan Martí-Carreras, Mandev S Gill, Cécile Meex, Sébastien Bontems, Emmanuel André, Marius Gilbert, Conor R. Walker, Nicola De Maio, Nuno R Faria, James Hadfield, Marie-Pierre Hayette, Vincent Bours, Tony Wawina-Bokalanga, Maria Artesi, Guy Baele, and Piet MaesMolecular Biology and Evolution, Mar 2020Since the start of the COVID-19 pandemic, an unprecedented number of genomic sequences of SARS-CoV-2 have been generated and shared with the scientific community. The unparalleled volume of available genetic data presents a unique opportunity to gain real-time insights into the virus transmission during the pandemic, but also a daunting computational hurdle if analyzed with gold-standard phylogeographic approaches. To tackle this practical limitation, we here describe and apply a rapid analytical pipeline to analyze the spatiotemporal dispersal history and dynamics of SARS-CoV-2 lineages. As a proof of concept, we focus on the Belgian epidemic, which has had one of the highest spatial densities of available SARS-CoV-2 genomes. Our pipeline has the potential to be quickly applied to other countries or regions, with key benefits in complementing epidemiological analyses in assessing the impact of intervention measures or their progressive easement.

-

Stability of SARS-CoV-2 phylogeniesYatish Turakhia, Nicola De Maio, Bryan Thornlow, Landen Gozashti, Robert Lanfear, Conor R. Walker, Angie S. Hinrichs, Jason D. Fernandes, Rui Borges, Greg Slodkowicz, Lukas Weilguny, David Haussler, Nick Goldman, and Russell Corbett-DetigPLOS Genetics, Mar 2020

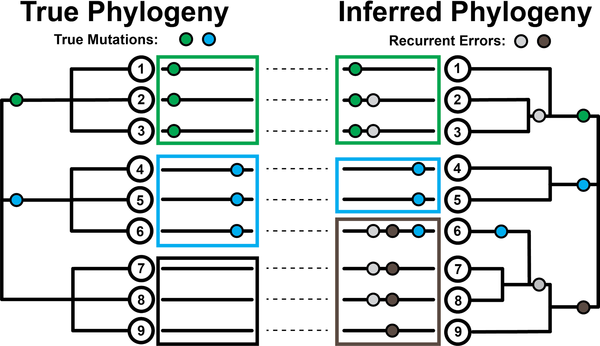

Stability of SARS-CoV-2 phylogeniesYatish Turakhia, Nicola De Maio, Bryan Thornlow, Landen Gozashti, Robert Lanfear, Conor R. Walker, Angie S. Hinrichs, Jason D. Fernandes, Rui Borges, Greg Slodkowicz, Lukas Weilguny, David Haussler, Nick Goldman, and Russell Corbett-DetigPLOS Genetics, Mar 2020The SARS-CoV-2 pandemic has led to unprecedented, nearly real-time genetic tracing due to the rapid community sequencing response. Researchers immediately leveraged these data to infer the evolutionary relationships among viral samples and to study key biological questions, including whether host viral genome editing and recombination are features of SARS-CoV-2 evolution. This global sequencing effort is inherently decentralized and must rely on data collected by many labs using a wide variety of molecular and bioinformatic techniques. There is thus a strong possibility that systematic errors associated with lab—or protocol—specific practices affect some sequences in the repositories. We find that some recurrent mutations in reported SARS-CoV-2 genome sequences have been observed predominantly or exclusively by single labs, co-localize with commonly used primer binding sites and are more likely to affect the protein-coding sequences than other similarly recurrent mutations. We show that their inclusion can affect phylogenetic inference on scales relevant to local lineage tracing, and make it appear as though there has been an excess of recurrent mutation or recombination among viral lineages. We suggest how samples can be screened and problematic variants removed, and we plan to regularly inform the scientific community with our updated results as more SARS-CoV-2 genome sequences are shared (https://virological.org/t/issues-with-sars-cov-2-sequencing-data/473 and https://virological.org/t/masking-strategies-for-sars-cov-2-alignments/480). We also develop tools for comparing and visualizing differences among very large phylogenies and we show that consistent clade- and tree-based comparisons can be made between phylogenies produced by different groups. These will facilitate evolutionary inferences and comparisons among phylogenies produced for a wide array of purposes. Building on the SARS-CoV-2 Genome Browser at UCSC, we present a toolkit to compare, analyze and combine SARS-CoV-2 phylogenies, find and remove potential sequencing errors and establish a widely shared, stable clade structure for a more accurate scientific inference and discourse.

-

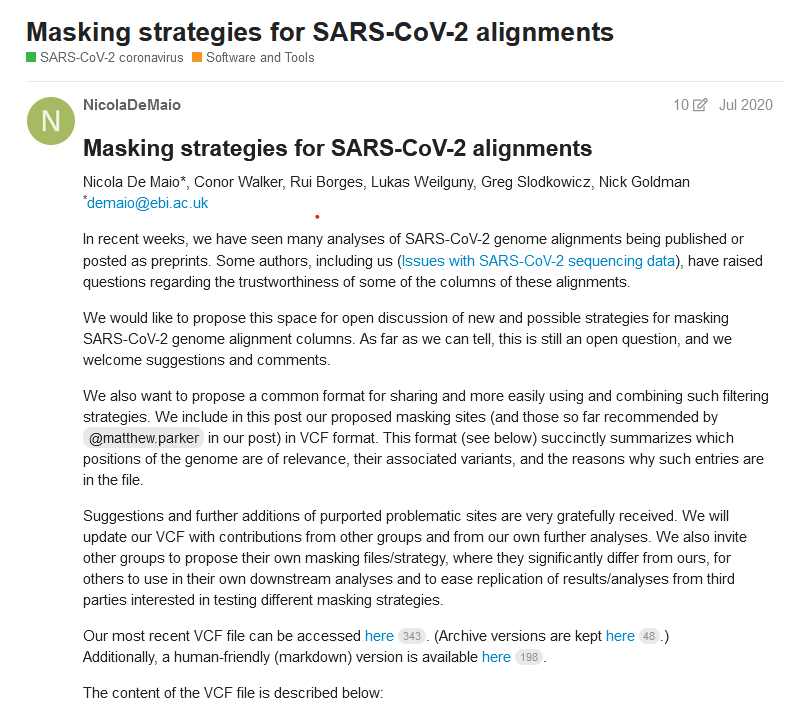

Masking strategies for SARS-CoV-2 alignmentsNicola De Maio, Conor R. Walker, Rui Borges, Lukas Weilguny, Greg Slodkowicz, and Nick Goldmanvirological.org, Jul 2020

Masking strategies for SARS-CoV-2 alignmentsNicola De Maio, Conor R. Walker, Rui Borges, Lukas Weilguny, Greg Slodkowicz, and Nick Goldmanvirological.org, Jul 2020In recent weeks, we have seen many analyses of SARS-CoV-2 genome alignments being published or posted as preprints. Some authors, including us (Issues with SARS-CoV-2 sequencing data), have raised questions regarding the trustworthiness of some of the columns of these alignments. We would like to propose this space for open discussion of new and possible strategies for masking SARS-CoV-2 genome alignment columns. As far as we can tell, this is still an open question, and we welcome suggestions and comments. We also want to propose a common format for sharing and more easily using and combining such filtering strategies. We include in this post our proposed masking sites (and those so far recommended by @matthew.parker in our post) in VCF format. This format (see below) succinctly summarizes which positions of the genome are of relevance, their associated variants, and the reasons why such entries are in the file. Suggestions and further additions of purported problematic sites are very gratefully received. We will update our VCF with contributions from other groups and from our own further analyses. We also invite other groups to propose their own masking files/strategy, where they significantly differ from ours, for others to use in their own downstream analyses and to ease replication of results/analyses from third parties interested in testing different masking strategies.

-

Issues with SARS-CoV-2 sequencing dataNicola De Maio, Conor R. Walker, Rui Borges, Lukas Weilguny, Greg Slodkowicz, and Nick Goldmanvirological.org, May 2020

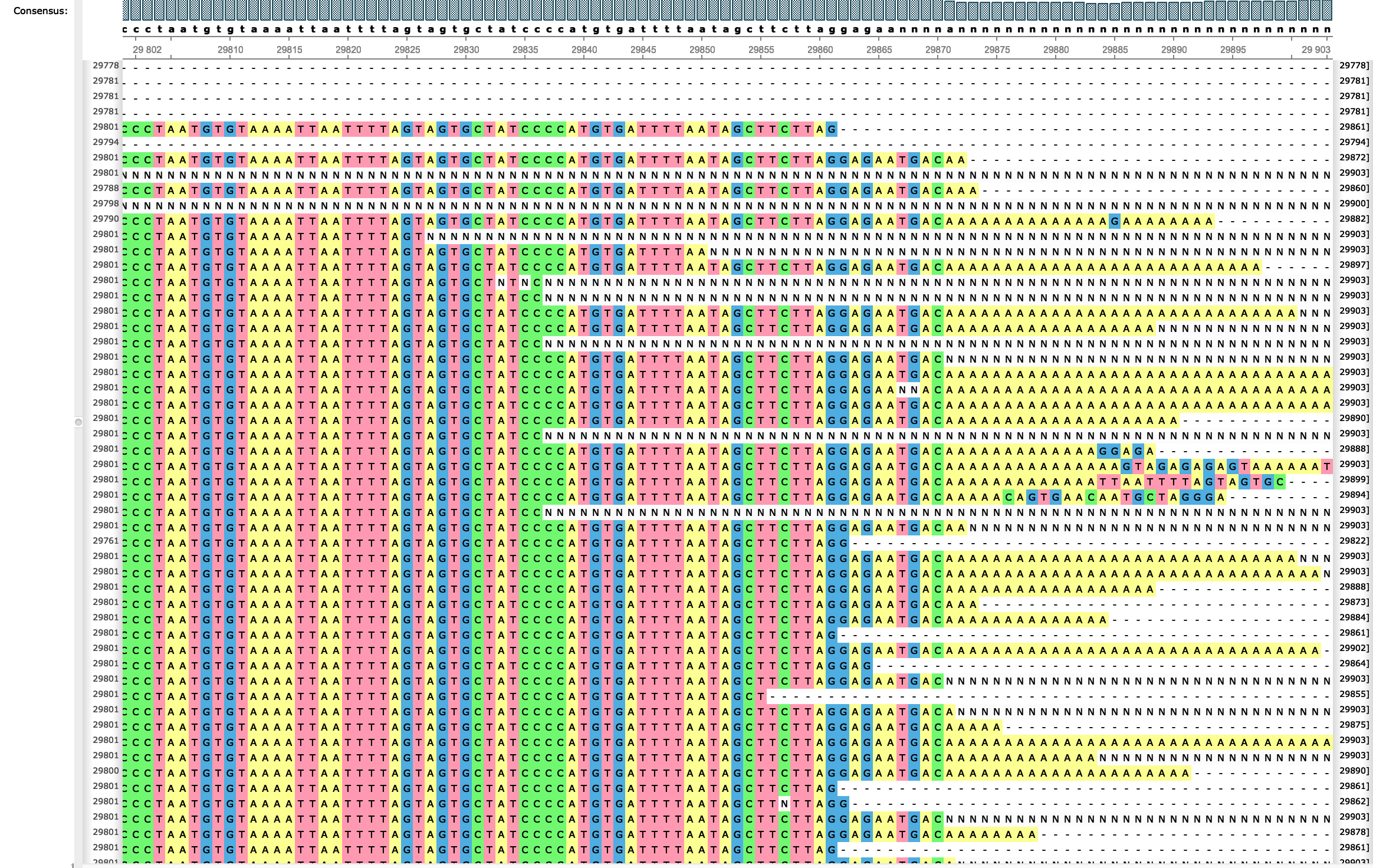

Issues with SARS-CoV-2 sequencing dataNicola De Maio, Conor R. Walker, Rui Borges, Lukas Weilguny, Greg Slodkowicz, and Nick Goldmanvirological.org, May 2020We investigate oddities in the SARS-CoV-2 genome sequences from GISAID. Many putative sequencing issues seem specific to genomic ends and to certain samples, and are easily filtered out. However, many mutations seem to arise many times along the phylogenetic tree (are highly homoplasic), and seem more likely the result of contamination, recurrent sequencing errors, or hypermutability, than selection or recombination. Some homoplasic substitutions seem laboratory-specific, suggesting that they might arise from specific combinations of sample preparation, sequencing technology, and consensus calling approaches. To help other researchers in similar efforts or who rely on available SARS-CoV-2 genome sequences in downstream analyses, we summarize the steps that we have recognised so far useful for filtering and masking alignments of SARS-CoV-2 sequences. We also hope that this will spark a discussion regarding the best methods to identify and interpret such peculiar variants and samples, and we provide here a list of filters that so far we think reasonable. First, we propose to mask alignment ends (as most of us already do), which are affected by low coverage and high rate of apparent sequencing/mapping errors. We mask positions 1–55 and 29804–29903 when aligned to reference MN908947.3, but other more or less stringent choices are possible. Secondly, we propose masking sites that appear to be highly homoplasic and have no phylogenetic signal and/or low prevalence – these can be recurrent artefacts, or otherwise hypermutable low-fitness sites that might similarly cause phylogenetic noise. A current list of these is: 187, 1059, 2094, 3037, 3130, 6990, 8022, 10323, 10741, 11074, 13408, 14786, 19684, 20148, 21137, 24034, 24378, 25563, 26144, 26461, 26681, 28077, 28826, 28854, 29700. We provide technical details of how these sites were identified below, however please note that all lists of sites outlined here are a work in progress, and might be affected by many choices made in the preliminary phylogenetic steps. In addition, we suggest masking any homoplasic positions that are exclusive to a single sequencing lab or geographic location, regardless of phylogenetic signal. Here the phylogenetic signal might be caused by a common source of error (among other things). Our current list is: 4050, 13402. We also recommend masking of positions that, despite having strong phylogenetic signal, are also strongly homoplasic. These may be caused by hypermutability at certain positions, although it is hard to rule out any possibility for now. Our current list is: 11083, 15324, 21575. Finally, as other groups have already suggested (see e.g. [12]), we recommend filtering out sequences that: have too few resolved characters (our somewhat arbitrary threshold is about 29,400 reference bases), are too diverged (as can be tested using TreeTime), have unusual locally high divergence (as can be tested using ClonalFramML), have missing/incomplete sampling date information, or that are distant from any other sequence in the dataset (we use a custom script to remove all sequences that are at least three substitutions away from any other sequence). We don’t provide a current list as this is quite long and varies as the number of publicly shared SARS-CoV-2 genome sequences increases.